Decolonizing Governance: A Personal Reflection from a Rural Courtroom

Prompted by a meeting with the District Attorney Fulton County in Georgia State, US.

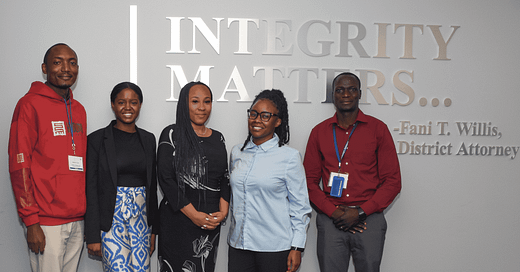

A few days ago, I had an honour, together with colleagues, (police officers from Malawi and Madagascar, and a legal aid defense lawyer from Namibia) to interact with the District attorney for Fulton county that also covers Atlanta, Georgia, Ms. Fani T. Willis, and oh boy, isn’t she solid! (You may want to Google her name after reading this.)

The interaction was warm. We were able to peer into the bad and the good of the American criminal justice system. That however is not my sharing today. The interaction with her just provoked thoughts around various themes like the colonial legacy.

The U.S like Uganda was colonized by the British, you cannot however say they run the common law system. They do, actually, but have clearly tampered it to meet their circumstances. But I digress. Let me get to today’s business.

The word “decolonize” is used frequently in different contexts. Its meaning changes depending on where and how it is used. But in this essay, I want to focus on a simple and straightforward meaning.

Uganda, like most African countries, was once colonized. Colonization did not just involve taking control of our land and resources. It also meant replacing our traditional systems of governance with those of the colonial powers. After years of resistance, independence was eventually won or granted. But political independence was just the beginning. What followed needed to be more than simply replacing colonial rulers with local ones. We needed to review and reform the systems left behind shaping them into structures that fit the needs, values, and cultures of our people.

Colonial governance systems were built on the idea that Africans were not citizens, but subjects. Sometimes they were even treated as if they were not fully human. These systems were not designed to protect rights or to serve the people. Instead, they were harsh, extractive, and aimed at control. It is no surprise that many people resisted them.

After independence, the big question was whether our leaders were able to remove or change these colonial systems. Sadly, in many cases, the answer is no. Most of what changed was who held power, but not how that power was exercised.

Look at the systems we inherited: the Executive, Legislature, and Judiciary. We talk about democracy, separation of powers, the rule of law, and regular elections. But have these structures really evolved to match the reality of our people? Or are we still trying to fit into systems that were never meant for us?

It is important to understand that governing African countries is a difficult task. Many of our countries were created by colonial powers with little regard for cultural or tribal boundaries. Also, most if not all post-colonial African leaders were trained in Western schools and institutions, and they returned home believing that the systems they had learned about were the best and only way to govern. Yet building a truly functional system takes time, effort, and honesty. Some societies spent centuries shaping their governance structures. We inherited ours almost overnight and often without understanding how to make them work for our people.

As someone who works in the judiciary, I want to focus on the administration of justice. About four years ago, I became a judicial officer (a Magistrate Grade One). This was a dream come true. I had joined law school hoping to one day become a judge who makes fair and just decisions like Solomon. That dream was influenced by my upbringing and my early passion for justice.

While at the Islamic University in Uganda, due to multiple issues I believed we could resolve through leadership, I became active in student leadership, and later youth leadership in Uganda. We worked on several important issues and achieved much. But over time, I became discouraged. Politics had its limits, and I began to feel I could make more impact by returning to my original dream of being a judicial officer.

God brought the opportunity after COVID 19. I was posted to Kibuku Magistrate’s Court, which serves Kibuku District with a population of over 250,000 people. However, it did not take long for me to realize that ordinary Ugandans do not understand what happens in court, and many of them do not trust or even like the system. Often, I felt like I was acting out a role in a play by leading processes, and making decisions that followed the law but made little sense in the eyes of the people.

Let’s consider some examples. One of the biggest challenges is language. In Uganda, English is the official language of the courts. Yet the majority of court users cannot speak or understand it. This means court proceedings often rely on interpreters. Unfortunately, interpreters many times make serious mistakes. As someone who speaks Lugisu and Luganda, and who understands Lugwere most spoken in Kibuku, I often notice that what is being interpreted is different from what is actually said by a party, a witness or myself. Sometimes the meaning is completely lost.

I then wonder what would happen if I didn’t understand the language at all or, how someone in court feels when they do not understand a single word being said in a matter that deeply affects them.

Then there are cultural challenges. These became clear when looking at the outcomes of criminal cases. According to the law in Uganda, the primary goal of the prosecution is to secure a conviction and ensure that the offender is punished. This is what the criminal justice system aims for. But when you speak to actual complainants, the victims, you realize their main concern is usually compensation.

If someone steals a cow, the victim wants the cow back first and foremost, or at least to be paid for it. If someone is assaulted, the victim wants their medical costs covered and to be compensated for the pain and suffering. Yet the law sees such cases as criminal, not civil. And it tells the victim that they are just a witness. If they want compensation, they must file a separate civil case, something many people cannot afford and do not appreciate especially when they learn that the civil Court is the very Court that heard the criminal case. It looks like a circus.

This approach confuses and frustrates many Ugandans. It also ignores the way justice traditionally worked in African societies. There, all wrongs were seen as injuries that required compensation, healing, and, where necessary, punishment. Offenders were dealt with in the community, not through isolation in prison. Serious crimes could lead to banishment, but not usually imprisonment. Justice was not about revenge. It was about restoring peace and dignity.

Now consider the financial cost. In the British system, that we have inherited, the government pays for investigations and prosecutions. But in Uganda, victims are often left to cover transport costs for witnesses, and other expenses like fuel for “you know who.” Then they are told in court that the case is not theirs, and they may need to open another file in a different court if they want compensation. They always raise these claims for costs and we shut them down, and some times threaten them with prosecution because some of those expenses are criminal yet open secrets.

Even worse, there is no law firm or legal aid office in Kibuku, and many other such districts. The nearest lawyer for Kibuku is 50 kilometers away in Iganga or Mbale. Hiring them can cost more than what many people earn in a year. The result is a system that denies justice to the very people it was meant to serve.

Faced with all this, with some energy from leadership in student, youth and civic spaces, I began to ask myself what I could do within my station and means as a Magistrate. I started to implement small changes, which turned out to be surprisingly effective, and that have encouraged me to think that we can do something.

First, I began using local languages wherever permissible and possible during court sessions in explanation of key aspects of Court processes. This has helped people understand what is happening, what their rights are, and what is expected of them.

Second, during criminal trials, if the prosecution does not talk about compensation, I ask witnesses directly but also give the accused a chance to respond through cross examination or remind them to do during their defence if they are not represented. If there is clear evidence, I then use my legal authority to order compensation. And before passing a sentence, even after hearing the prosecution, I insist on hearing from the complainant to also factor in their input. Often times, the interests of the Prosecutor, and the victim are at variance.

Third, I encourage mediation. This is more so for civil and small claims matters. The most successful procedure in my court is small claims resolved mostly through simple payment plans. These allow both parties to go home satisfied.

Fourth, I use technology to speed up the writing of rulings and judgments thanks to being technologically literate and enthusiastic. We also carefully reviewed pending cases to remove those that were no longer active. As a result of all these strategies, we cleared the case backlog. There is no case older than two years at Kibuku Magistrate’s Court.

Fifth, we tried to help people understand court procedures. At first, we put up posters around the Court. But we realized that most people cannot read. So we have created audio messages in local languages, explaining how the court works and what services are available.

Sixth, we trained court staff in customer care. Many people fear the court environment, even though it should be a place of help and healing. We are working to change that culture.

Seventh, we created a service called “Ask the Magistrate,” where people can come to ask legal questions even if they do not have a case. Some people bring their disputes, and we help guide them toward resolution.

Eighth, before starting the Court sessions, we do some sensitization about basic legal issues, that we also take to radio, and every opportunity we get with the community like during land case locus visits.

These may be small steps, but they show what is possible when we take time to reflect on what works for our people. Many of the problems in our system persist because we copy and paste solutions from other countries without asking whether they fit our context.

To be fair, the Judiciary in Uganda has taken some helpful steps. The introduction and promotion of alternative dispute resolution, small claims procedures, and other reforms shows that some colonial-era barriers are being slowly removed. But more could be done especially by Parliament. The question is whether our lawmakers truly understand the needs and values of ordinary Ugandans.

Do citizens truly feel connected to Parliament and the work it does? That question remains open.

For now, this reflection must pause here. But the conversation will continue.

Thank you.

Still, Uganda has not sat passively in disappointment. The country has birthed generations of thinkers, artists, entrepreneurs, and educators who have taken up the mantle of reimagining society. Teachers who challenge colonial epistemologies. Business owners who root their practices in local wisdom. Leaders who envision community-centered governance.

Nine : your YouTube channel that helps people to know the law, This has been of a great importance to me to understand the law

Ten: Don’t you think we need to replace most of the literature books in both our primary and secondary schools with the Ugandan constitution?…if we achieve this I believe this will help courts and citizens to differentiate btn a civil case to criminal case(Focus Sir on This it’s very important)

Eleven:Decolonization has not been handled properly in Your Eight points

To me I feel yo massaging the real issue with yo personal achievements in Judicial office…But decolonization is bigger and a risky topic most especially in our modern world (Governance)

Twelve:you can never be good in a broken system..The Ugandan Judicial system is just broken,personalized very backward and it deserves no respect like what courts of law or Justice deserves Worldwide (Focus on This)